| NERVOUS

SYSTEM |

|

The

random

route to

perfect poise |

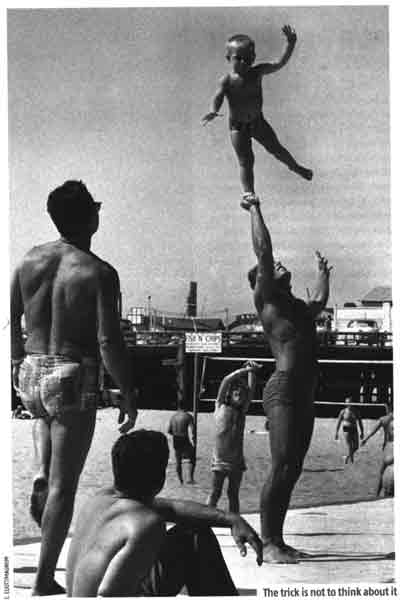

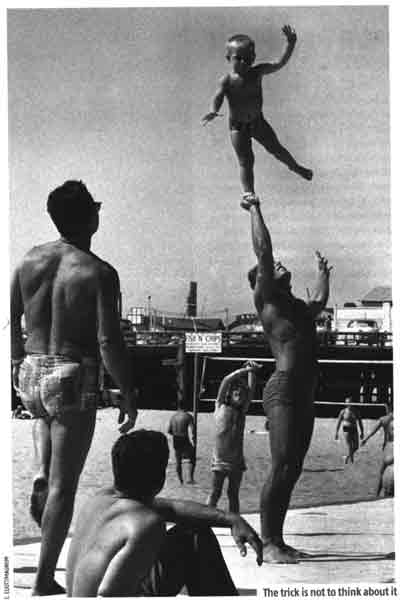

THERE's

more to balancing acts than poise and sharp reflexes. The secret to tasks

such as balancing a stick on the end of your fingertips is random noise

generated by the nervous system. The finding is changing

scientists' views about how the body controls movement.

According

to physicist Juan Cabrera of the Institute for Scientific Research in

Caracas, Venezuela, and neurologist John Milton of

Chicago University, random hand movements correct

a stick's wobbles far faster than a person would

be able to react to seeing them.

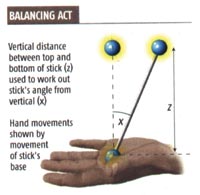

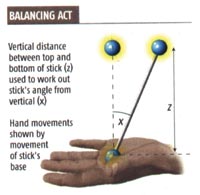

Cabrera and Milton developed the idea by capturing the balancing

act on film. By watching light reflected from the ends of the stick

they measured the size of the wobbles and correlated

them with people's hand movements (see

graphic).

|

| "We

couldn't think of a better experimental paradigm to study how the nervous

system controls balance on short timescales,"

says Milton. They found that although it takes 100 milliseconds for someone

to react to a visual cue like a wobble,

98 per cent of the hand movements used to keep the stick upright

happened faster than that (Physical Review |

Letters,

vol 89, p158,702).

To understand the result, the researchers used mathematical equations

to describe the motion of the stick, based on ones describing a similar

system involving an upright rod pivoting at its base, called an inverted

pendulum. They simulated the hand movements by adding a random "restoring

force" to their equations. They found that this |

therefore be tuned to keep

the stick very close to the point of instability. Random hand movements

in every direction cancel out the wobbles so the stick stays upright,

enabling the body to do a task for which normal reactions would be too

slow.

The finding is causing neuroscientists to rethink

their ideas about motor control in

|

|

random force

was enough to keep the stick upright, making it wobble just like the real

thing - but only if the stick was on the verge of toppling over.

Cabrera and Milton suggest that the nervous system

must |

general. "Our

experiment suggests that the control of movements is organized on the

edges of stability," says Milton. "This is about as big a change

in how one should think about things that I can imagine." |

|